For decades, analysts of Ethiopia’s political conflicts have focused on ethnicity and federation. The Tigray war, the Oromo insurgency, Somali regional dynamics, or Afar–Amhara competition take up most of the scholarly oxygen. Yet that lens overlooks an increasingly central driver of elite behavior and mass mobilization in contemporary Ethiopia: religion. In particular, the rise of Pentecostal Christianity to the centre of power through Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and the Prosperity Party (PP) has created a new axis of conflict that cuts across ethnic lines, sometimes reinforcing and sometimes undercutting them.

Ethiopia has never been secular in a Western republican sense. The imperial state was deeply rooted in Orthodox Christianity. Menelik II and Haile Selassie both fused imperial sovereignty with Orthodox legitimacy. The Derg attempted to destroy this model, but produced no viable ideological replacement. When the TPLF-led EPRDF took power in 1991, it pursued a more technocratic secularism: religion was not entirely removed from politics, but it was bracketed away from the state’s main ideological narrative, which was derived from Marxist-Leninist federal developmentalism. Religion flourished socially in this vacuum, especially evangelical Protestant denominations, which were not historically tied to state power or hierarchical ecclesiastical structures.

Pentecostalism – imported mainly through American missionaries, trans-African networks, Ethiopian diaspora returnees, and local revival movements – experienced remarkable growth from the 1990s onward. By the mid-2010s, Pentecostal discourse had become dominant in Addis Ababa’s educated urban middle class. Importantly, it is a religious style that aligns well with Ethiopia’s new elite generation: individual salvation, meritocracy, entrepreneurialism, a belief in personal calling, and a prosperity theology that sanctifies material success. This is not incidental — this is the sociological soil from which Abiy emerged.

When Abiy came to power in 2018, his evangelical background was immediately visible. His language — about “medemer,” synergy, positive thinking, forgiveness, and national resurrection — was heavily infused with Pentecostal codes. Many foreign observers misread this as merely “new age optimism.” In fact, it was theological. Abiy’s circle includes pastors, preachers, and charismatic leaders. The Mekelle peace rally in 2018, the stadium gatherings in Addis, the use of music and prayer in state ceremonies — all signalled the emergence of a new performative mode of political spirituality.

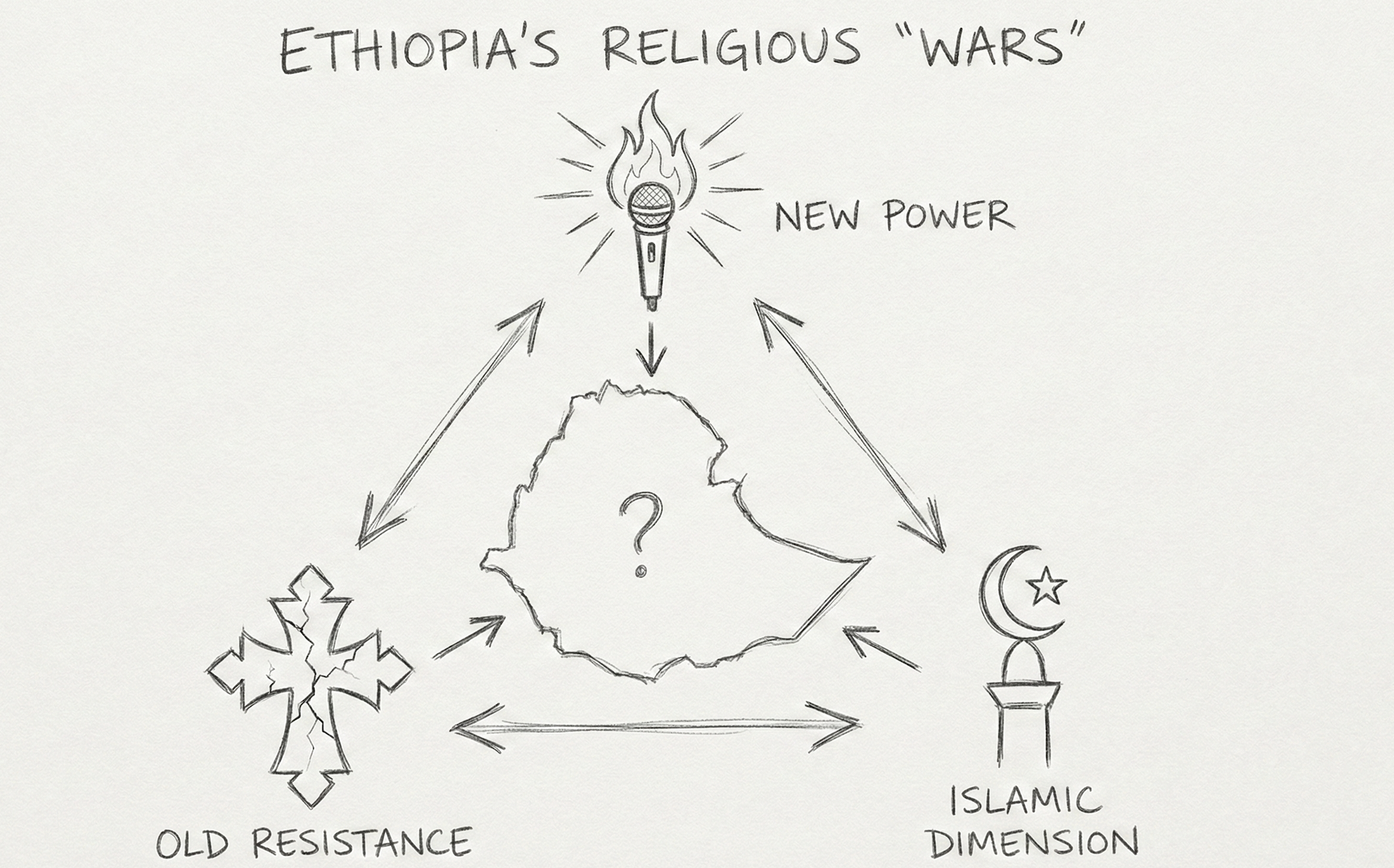

This is the context in which today’s religious “wars” must be understood.

The Orthodox Church as Counter-Power

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (EOTC) remains a massive institution, with extensive land holdings, substantial wealth, a robust media presence, and millions of believers deeply embedded in rural society. For most Orthodox clergy, Abiy’s Pentecostalism is not just theologically alien; it is a direct assault on an entire civilizational identity. The EOTC carries the memory of empire, the Semitic Christian narrative of Ethiopia as a “chosen nation,” and an ancient liturgy.

Abiy first embraced the Orthodox Church as the basis of legitimacy in his speeches and conversations. Gradually, however, Ethiopia has started to frequently host official visits by rival religious movements, Pentecostal preachers and prosperity advocates with direct state-level visits and invitations. This was also followed by massive narratives of prosperity spirits, which are alien to the Ethiopian political, cultural and religious societal context. Abiy employed three essential methods to neutralise the Orthodox Christian reaction to defuse the new version of spiritual narrative deep into the Ethiopian cultural and religious context. First, pulling marginalised ethnic groups into the palace; Second, sympathising with marginalised religions (Muslims and Protestants) while systematically denouncing Orthodox dominance and making it equal the rest of the two religions; and finally, creating intra-Orthodox cracks along ethnic lines (primarily rivalry and war between Tigray and Amhara), which are the basis of Orthodox Christianity.

Abiy effectively polarised the Orthodox Church by placing it in the War in Tigray when the Bishops from the Amhara ethnic group in the federal Synod explicitly supported and advocated the war. It consequently resulted in the complete dissociation of the Tigray Orthodox Church and the establishment of a new Synod; the Synod of the Tigray Orthodox Tewahedo Church, rejecting the Ethiopian Synod and termination of continuity under one dogmas and preaching practices. The Oromo Synod also goes a long way toward dissociating itself from the Amhara-narrative-dominated Ethiopian Synod. This might be considered as a critical time in history when the Ethiopian Orthodox Church is severely contested in its internal unity and continuity. It is interesting that while Pentecostal crosses ethnic lines in mobilising along new spirits, the Orthodox Church fractures from within along ethnic lines and is suffocated from outside by other rival religions and political pressures.

Moreover, the methodology also exploited the anti-modernisation backward structures and practices of the church to which a significant elite and younger generation can easily subscribe. This move was followed by cultural shocks defused from above via gospel preachers and prophecy-making pastors, which fractured the long-standing, untouchable, solid Orthodox Christianity narrative and an omnipotent presence in Ethiopia.

Therefore, clashes between the government and Orthodox authorities after 2023 over questions of Synod legitimacy, regional bishops, and state interference in church administrative appointments reflected a structural power struggle: not merely administrative quarrels, but a battle over which religious narrative sanctifies Ethiopian statehood.

Many Amhara political elites interpret Abiy’s religious orientation as part of a longer effort to “de-Amharise” the ideological state project — replacing imperial Orthodox symbols with post-ethnic prosperity rhetoric rooted in Pentecostal individualism. That is why religious protests in the Amhara region, which began in 2023, have become indistinguishable from anti-government demonstrations. For many parishioners, resistance to PP is not primarily a matter of politics. It is a defence of Ethiopian civilisation.

However, the marriage of Amharanization and Orthodox Christianity appears weakened in mobilising across ethnic lines as it did historically, because its legitimacy has been miserably downgraded in recent Ethiopian crises, as spiritual authority is increasingly balanced against political instrumentalisation. This, in turn, provided fertile ground for advancing Pentecostalism without significant challenge, as it has been doing in recent years, which would otherwise be difficult in Ethiopia. Still, the ethnic contestation between Oromo-Amhara-Tigray (major ethnic groups) will continue along ethnic lines, and Orthodox Christianity will not be a significant uniting factor among them. Hence, Pentecostalism will continue to take advantage of intra-Orthodox unsettled rivalry along ethnic lines and its immunity from biased background association, which the Church has been frequently criticised for since history to date.

Pentecostalism Cross Ethnicity Leverage

Pentecostalism is not “Abiy’s ethnic religion,” however, which is one of its main advantages for political deployment. It is not an Amhara thing, nor an Oromo and Tigray thing. It is flexible across identity cleavages. Prosperity theology, the promise of personal breakthrough, the centrality of the Holy Spirit — these are trans-ethnic messages that resonate with youth in Hawassa, Bishoftu, Dire Dawa, Bahir Dar, and even Jigjiga. Ethiopian evangelical music is one of the most consumed cultural products in the country. Millions watch church live streams on TikTok and YouTube.

Pentecostalism has also emerged at a critical time, when the young generation across all Ethiopian regions is receptive to a new vision of life as an exit from the economic and conflict-shattered desperation. Their loss of hope in the business-as-usual routines and traditional paths of Orthodox Christianity cannot accommodate the rising aspirations and visions of life of the younger generation, with higher exposure to international standards of lifestyle via digital technologies and other communication infrastructures. The designers of Pentecostalism's expansion to Ethiopia have picked the proper timing as a broader agenda of defusing liberalisation by shocking the reactionary cultural and religious statuesque for two essential reasons. One, they have found out that Abiy Ahmed, a leader who has delicately committed himself to implementing the project at any cost. Second, Ethiopia’s tight religious bonds are softened due to the Grand National shocks of conflict, intra-Orthodox polarisation and economic crisis that transcends strict upholding of religious boundaries by the new generation.

The rise of Pentecostalism is therefore not simply a top-down project of Abiy. It is a deep sociological trend — and Abiy is merely its most visible political face.

However, where Pentecostalism serves as a cultural glue, it also generates backlash. Orthodox believers see “Americanisation.” Muslims see an attempt to convert the state into a Christian state under a charismatic leader. Even within evangelical groups, there is discomfort with the intensity of political sacralisation of the office of the Prime Minister.

In other words, Abiy’s religion does not pacify Ethiopia. It re-sorts conflict lines.

The Muslim Dimension

At first glance, Muslims have been less directly involved in these religious wars—partly because the state is not Muslim, and partly because Islamic elites have been more cautious about overt political confrontation since the 2012–13 crackdown on the Muslim protest movement. Furthermore, Muslim elites have been sympathetic to Abiy’s leadership, viewing him as a Muslim leader for the first time in modern Ethiopian history and seeing it as an advantage. He gained their support by positioning them equally with Orthodox Christians in the public sphere of his governance. However, concerns are growing as circumstances shift. Northern Muslim communities in Amhara and Afar associate the Prosperity Party with a Christian-led revival of the state. Southern Muslim groups are worried about Pentecostal influence in education.

Muslims in contemporary Ethiopia have the leverage to exploit the opportunity presented by Arab states' massive capital investment in the country, which goes far beyond mere economic interests in the Horn of Africa. Ethiopia to remain a Christian-dominated state in the heart of the Horn of Africa is not in the interest of the Arab states and the Muslims in Ethiopia. Even though the Prosperity Party's systematic neutralisation of the Orthodox Church was a welcome incident for Muslims, its quick replacement by the Pentecostal liberal orientation aggressive movement is not good news. Lack of security guarantees for their believers and praying mosques in different parts of Ethiopia further posed hesitation among the Muslims.

The 2023 burning of mosques in several locations across the country, including in Gondar, were not isolated events but symptoms of an increasingly combustible religious landscape.

The Return of Sacred Politics

The Ethiopian state is not secular in practice today. It is not imperial Orthodox either. Instead, it is becoming charismatic-theological. Abiy’s political speeches have become sermons. The “National Dialogue Commission” meetings incorporate prayer and gospel music. The GERD is narrated as a spiritual destiny project.

This fusion is extremely potent — because it makes political disagreement heresy.

If Abiy is a divinely called leader, if prosperity is God’s plan for Ethiopia, then critics are not political opponents. They are agents of darkness, forces of division, people without “medemer spirit.” This is where Ethiopia’s religious “wars” become dangerous: the opponent is not just wrong — he is spiritually misaligned.

Conclusion

Ethnicity will not vanish as Ethiopia’s primary battlefield. But it is no longer sufficient to understand political legitimacy. The 1994 federal model assumed that ideology would structure politics and that ethnicity would structure administration. Today, religious identity is becoming the deeper source of meaning — and of conflict.

The new Ethiopian elite is Pentecostal. The old hegemonic elite is Orthodox. The Muslim bloc is anxious but cautious. And the state sits inside this triangulation with a leader who openly sacralises governance.

In this landscape, Ethiopia’s future instability may not be driven solely by territorial disputes or debates over federalism. It may be driven by theology — and by a struggle over which religious cosmology animates the idea of Ethiopia itself. This development will be further complicated by the heavy penetration of the Middle East Islamic states, the diffusion of cultural liberalisation from the Pentecostal movement, and the reaction from Orthodox Christians to maintain the status quo. Therefore, the long-standing rivalry between Muslims and Orthodox will further expand to include the new Pentecostal movement in Ethiopia, which is challenging all of these pre-existing religions in the current political landscape. It, in turn, will invite strategic actors to exploit this opportunity for their respective geo-economic, security, and cultural dominance interests in the heartland of the Horn of Africa, Ethiopia. This rivalry will undermine Ethiopia’s national unity and regional security dynamics.

.png)